While in history books it might seem as though the transition from the Ming dynasty to the Qing dynasty was virtually immediate, it actually took a number of years for the Manchus to establish themselves as the new rulers of China. As a result, people of the time had to live through this time of dramatic change, and had to contend with the differences it brought up in their lives. The cultures of the Han Chinese and the Manchus were quite different, as the story of the Manchurian Princess Fodo attests. As a woman living in China, she had to face social pressures that did not exist in Manchuria, and encountered and had to adapt to differences in lifestyle and spiritual beliefs. Her husband, Wu Ximen, son of Wu Sangui, also dealt with the difficulties of the Chinese men who defected to the Qing banner-men. The loyalties of these men were tested between the Chinese people and culture they grew up with, and the Qing emperor that they had sworn loyalty to. This was especially true in the case of Wu Ximen, when his father chose to revolt against the Qing, an event that decided the fates of Wu Ximen and Fodo.

In 1616, the Manchus (then known as the Jurchens) were dominated by Nurhachi of the Aisin Gioro clan, who began to refer to himself and his followers as his own dynasty, the Later Jin1. The power of Nurhachi and his family continued to grow, and when he died in 1626, he was succeeded by one of his sons, Hong Taiji. Hong Taiji had a cousin named Eje, who, with his wife Maca, had a daughter in 1626, named Fodo, meaning “willow”. As a Manchurian girl, Fodo enjoyed a lot of personal freedom, often going on group hunts with her father and other members of the clan. She became extremely skilled at horseback riding, and it was one of her favorite pastimes. She loved the thrill of galloping through the expansive plains and forests of her homeland. However, life was about to change drastically for this freedom-loving girl and her family.

As time passed, Hong Taiji and his clan continued to amass power and land, and in 1636, Hong Taiji renamed the dynasty Qing and began referring to himself as emperor2. These decisions were clear signs that Hong Taiji and the Manchus had their eyes on the Chinese throne, and meant to conquer the territory ruled by the Ming dynasty. One point of conflict between the Ming and the Qing was Korea, since the Korean king declared support for the Ming in 1627. This declaration prompted an invasion of Korea by Qing forces, and a second invasion was initiated in 1637. This time, however, Fodo’s father was killed by an arrow in battle, and this was the first portent of change for her. From then on, Fodo’s mother tried to keep her more confined and tried teaching her sewing and weaving, but with little success. Always headstrong, Fodo often escaped from her home to go horseback riding. Since her father was dead and Fodo had no brothers, her uncle inherited her father’s title. He began to take responsibility for caring for the family, and Fodo continued to go on group hunts.

In 1643, Hong Taiji died suddenly and the dynasty was taken over by his younger brother Dorgon3. Dorgon led Qing forces in another invasion against the Ming, and this time it was a success. In May of 1644, afraid of the rebel forces of Li Zicheng, commander Wu Sangui opened the eastern gate of the Great Wall to Manchu army, who helped defeat the rebels and then headed to the capital Beijing4. Once Dorgon reached Beijing, he announced that the Qing had inherited the Mandate of Heaven from the earlier Ming dynasty, therefore declaring Qing the new dynasty of not just the Manchus, but of the Chinese as well. As further incentive for loyalty, Wu Sangui’s sons were given princesses from the Aisin Gioro clan as wives. His son Wu Yingxiong married a daughter of Hong Taiji5, and his son Wu Ximen was given Fodo as a bride, in return for joining the military banner-men of Dorgon. Soon after, Wu Sangui was sent to Nanjing, and Wu Ximen and Fodo followed, settling down in the southern capital.

Even after conquering Beijing, however, the Qing forces were not done fighting for control of the former Ming territory. In 1652 the loyalist forces of Zheng Chenggong had some military successes6, drawing the Qing forces out into battle and putting up a good fight even after suffering losses. The Qing offered settlements as they had for other loyalist forces7, but while Zheng seemed to go along with these negotiations, he soon broke off the talks and began fighting again. In 1658, Zheng Chenggong’s forces tried to invade the Yangzi valley in an effort to capture Nanjing8. Fed up with this rebel nuisance, the Qing put Wu Sangui in charge of eliminating all remaining Ming loyalists in the southwest9. Naturally, Wu Ximen was part of the Qing army under control of his father, and while Fodo stayed in Nanjing, he wrote back about the difficulty fighting these Chinese men. Unlike the chaotic rebels like those following Li Zicheng, Zheng Chenggong had a more organized force with a substantial claim to the Ming throne. Wu Ximen mentioned his own inner struggles about fighting armies loyal to an empire he once pledged loyalty to, but eventually the loyalist forces were defeated. In return, Wu Sangui was granted a large portion of land in the Yunnan province, which became one of the Three Feudatories10. Wu Ximen and Fodo travelled to live in the same city as Wu Sangui, and Wu Ximen was appointed to an official.

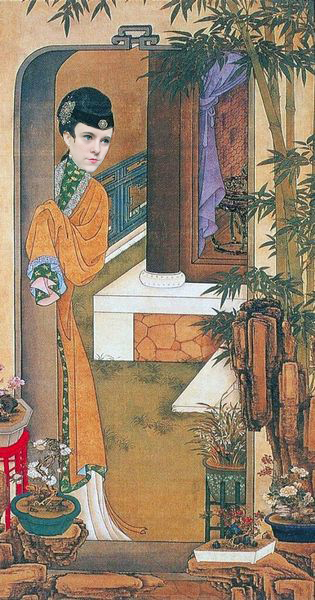

At first Fodo acted as she always had, as a highborn Manchurian woman, dressing in the Manchurian style and roaming about the city as she pleased. However, the more she interacted with married Chinese women in the families that Wu Ximen and Fodo befriended, she became more aware of how odd her behavior seemed to others, as there were few Manchurian women in the city. At one point, one elderly Chinese woman reprimanded Ximen for allowing her to behave in this exotic way, so Fodo began dressing in the traditional Chinese style of the south, and tried to conform to the expectations of a married Chinese woman. She spent more time with other Chinese women in order to learn more about their ways.

She noticed that the other women were more quiet and reserved around men, and that their interactions with their husbands seemed somewhat ritualistic, as did the interactions their maids had with them. When Fodo asked about this, the women told her about the teachings of Confucius, and about how a wife should always be submissive and subservient to her husband. These beliefs seemed so different from the Manchurian traditions of worshipping deities and nature11. Fodo could also not understand why the men complained to their wives about the queue hairstyle — to her it seemed like a prominent and honorable way to show loyalty to the Qing emperor, but the other women tried to explain how it went against the Confucian belief that one’s body, including one’s hair, is a gift from one’s parents, so to cut it off was to dishonor one’s parents12. At this remark, Fodo brought up the practice of foot binding. She asked if the practice of breaking and reforming the feet of girls was not also dishonoring one’s body and therefore dishonoring one’s parents. The other women laughed, saying that foot binding did not separate the parts of one’s body the way cutting one’s hair did, and that foot binding not only brought out the beauty of the womanly form, but it also demonstrated the woman’s dependence on her husband. Fodo still did not understand. She could not see the benefit in not being able to walk around town, or run, or ride horses because of one’s disfigured feet. But these ladies had never been on a hunt anyway, and they even said that such things were unladylike.

Because these women had little experience with the outside world, Fodo was shocked by their lack of knowledge about the society outside their inner chambers. They knew nothing about what was going on in the city and did not even seem to care, while Fodo always tried to listen in on conversations Wu Ximen had about the town’s goings-on. However, the women were very interested in reading poetry, watching plays, sewing, embroidering, and painting. Fodo had learned how to read the Mongolian and Chinese script, and was fluent in Manchurian and Chinese, but she never liked reading, preferring to spend her time outdoors instead. So while she somewhat enjoyed watching plays, she did not understand many of the literary references that the Chinese women found so entertaining, since she did not read many poems or other works of literature. Fodo tried to take up painting in order to fit in with the other women, but found herself staring at the artless landscapes she created, wishing instead to be riding out on real landscapes on horseback. Frustrated and bored, she wanted to escape her inner chamber. Not wanting for someone to remark to Ximen about Manchurian garb, Fodo tried going out in the city in her traditional Chinese clothes, but a maid recognized her and hurried her back to their home. So she tried other tactics, sometimes dressing up as a maid, sometimes dressing up as a man, just so she could leave the home unnoticed.

Fodo and Wu Ximen soon had two children, a boy named Lixin and a girl named Feiyan. When they were born, Fodo did not pay too much attention to them for years, focusing on her own adventures instead. So for the first few years of their lives, they were raised primarily by wet nurses. However, as the children continued to grow, Fodo saw that they had spirits of their own, and she spent more time with them. She told them stories about bravery and hunting in the Manchurian forests, and encouraged them to be physically active and pursue activities that interested them, regardless of what other people said. Her son in particular fell in love with the romantic stories that his mother told, and began to study the history of China as well as that of the Manchurians.

In 1673, the Kangxi emperor tried to dismantle the Three Feudatories, but the men in charge of them, including Wu Sangui, revolted, leading to a war13. Wu Ximen knew he had to make a choice. Out of loyalty to his father, he would stay and fight, but knowing the brutality of the Qing army, he feared for the life of his family. He made plans to send them away to stay with a friend of his in the northwest Shaanxi province, where they would be safe from the fighting. And if the Qing wanted to punish Wu Sangui’s family, no one would think to look for Fodo and her children so far north. As a further precaution, Fodo and her children would change their surname to Liu, a fitting name because it meant “willow” in Chinese just as the name Fodo meant “willow” in Manchurian. Fodo was ready to flee, wanting to distance herself and her family from the traitorous Wu Sangui, but she did not understand her husband’s decision to stay. She pleaded with him to flee with his family, to also change his name and find work in another city. In her mind, it did not make sense why anyone would betray the ruler, who, by Manchurian tradition, must be the most powerful person. Wu Ximen tried to explain his Confucian responsibilities as a son, but with no success. In the end, Fodo took his betrayal of the Qing as a personal betrayal as well, and left for Shaanxi with her children. Wu Ximen promised to return to her if he could, but neither really believed that this would happen.

In 1674, Wu Ximen’s brother, Wu Yingxiong, was executed by Qing forces14, and in 1678 Wu Sangui died of dysentery15, leaving Wu Ximen and his nephew Wu Shifan to continue the fight16. Early in 1681, however, Wu Ximen died in battle against the armies he had once fought with, and later that year Wu Shifan committed suicide, effectively ending the rebellion17. Since Fodo was so far removed from these events, it is unclear what she knew of her husband’s fate, but once she heard that the Qing were victorious over the Three Feudatories, and he still did not send for her, she knew that she would never see him again.

For the rest of her life, Fodo lived with the family of Zhang Weixian, Wu Ximen’s friend in Shaanxi. When Wu Ximen knew him, he had been an official in Beijing, but had since fallen out of favor with the emperor and was exiled to Shaanxi, where he eventually became a farmer. Because they lived in this rural town away from the high-class city, it was less strange for Fodo to be seen outdoors. Even though she had been torn away from the lifestyle she was accustomed to, and she had left all of her possessions and tokens of Manchurian culture behind in Nanjing, she now had more freedom, which mattered the most to her. She was even eventually able to buy a horse, and began riding again. Her daughter Feiyan stayed with her mother until she married the son of another farmer in the town. Feiyan and Fodo were both happy with the match, because it meant that they could see each other often and go horseback riding together. Her son, however, with the education he received as a child, travelled to Beijing to become a history tutor under his new name Liu Lixing. Because he had been so fascinated by his mother’s life, he studied Manchurian history intensely, and even wrote a biography of his mother, which is how so much information about her life has lived on. Fodo herself lived a long life, living through the destruction of the remaining loyalist Chenggong family in Taiwan in 168318, as well as the increase in Jesuit influence in China19, but none of this mattered to her, because she had her freedom, her children, and eventually her grandchildren. Throughout her life, she encouraged her children and grandchildren to be independent, until she died of natural causes in 1703, at 77 years old.

Endnotes

1 Hansen, Valerie. The Open Empire: A History of China to 1800. 2nd ed. N.p.: W. W. Norton, 2015. 391. Print.

2 Hansen 392

3 Hansen 393

4 Hansen 394

5 Crossley, Pamela Kyle. A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. Berkeley: U of California, 1999. 107. Print.

6 Wills, John E. Mountain of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1994. 226. Print.

7 Wills 224

8 Wills 227

9 “Wu Sangui”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 09 Dec. 2015 <http://www.britannica.com/biography/Wu-Sangui>.

10 Hansen 396

11 Hansen 290

12 Hansen 395

13 Hansen 396

14 Dzengseo, and Nicola Di Cosmo. The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-century China: “My Service in the Army” London: Routledge, 2006. 16. Print.

15 Encyclopædia Britannica

16 Dzengseo 16

17 Dzengseo 17

18 Wills 229

19 Hansen 396

BONNIE NORTZ is a double major in Mathematics and Linguistics, with a minor in Computer Science. This year she is a Take Five student for Chinese Language and Art. She is also involved in SOCKS and Swing Dance Club. More by Bonnie

BONNIE NORTZ is a double major in Mathematics and Linguistics, with a minor in Computer Science. This year she is a Take Five student for Chinese Language and Art. She is also involved in SOCKS and Swing Dance Club. More by Bonnie