Giuliano Vivolo was born in 1249 to a working class mother in Venice. Descending from an unknown father, and not having any other relatives besides his mother, Giuliano was an only child, who spent his early years in introspective silence. His mother, working as a maidservant at the time, tried her best to give her son an education, but being lowborn, she was unable to do so to an adequate extent.

Giuliano Vivolo was born in 1249 to a working class mother in Venice. Descending from an unknown father, and not having any other relatives besides his mother, Giuliano was an only child, who spent his early years in introspective silence. His mother, working as a maidservant at the time, tried her best to give her son an education, but being lowborn, she was unable to do so to an adequate extent.

As soon as her son reached the age of ten, in 1259, Giuliano’s mother approached her master, Maffeo of the Polo family, about a position for her son as an assistant to his brother, Niccolò, and himself, in their merchandise shop. While there, he would be able to further his studies in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Having been on the lookout for such a youth, the two Polo brothers happily struck a deal with Giuliano’s mother, and so the young Giuliano Vivolo came to move in with the at the time well-known Polo family.

What Giuliano’s mother had not considered while approaching her masters, however, was that only five years prior to her request, another member of the Polo family had come to see the light of day. This member, the youngest and newest addition to Giuliano’s new household was Marco, a charismatic and adventurous boy five years Giuliano’s junior.

The two had known each other before Giuliano, like his mother, had also started working for the Polo family, as his mother would also look to Marco during her time spent at the Polo family’s residence during the day. Giuliano’s mother would sometimes take her son with her, to work or to the local market, for example, and she would stop by the Polo residence to see how Marco was doing. During all this time, the two children had become acquainted with each other, and had struck up a good friendship.

With Giuliano being employed by the Polo family, Marco had now found a more permanent playmate, and the two would spend time together whenever Giuliano would not strictly be needed as an assistant in the merchandise shop of Marco’s family.

Nothing like himself at all, the young Marco Polo was charismatic, adventurous, always smiling, and so vigorous, it would take ten boys like Giuliano to even come close to compare to Marco. After the merchandise shop had closed, Giuliano would go and teach Marco what he had learned that day, and so Giuliano became a bit of an older role model for Marco, at least in regards to his studies.

Two years after Giuliano had joined the Polo family, in 1261, Niccolò and Maffeo left for their first journey to the East. It was left to Giuliano and the other apprentices working for the two brothers at the time to take over and continue what their masters had done before. Being the youngest of the apprentices, as he had only been accepted into service a couple years ago, Giuliano found himself with even more free time, as the older apprentices were willing, some particularly eager, to work more to prove their worth to their masters, once those would return from their travels. Giuliano, being only twelve at the time, did not care much for running the business (as he had found that he was not particularly good at keeping the numbers straight in his head), and took the opportunity to teach his new friend what he had learned. The two became even better friends than they had already been, and so they would spend increasingly more time together than apart.

Being in Marco’s company, Giuliano and his employers’ son wondered what the two Polo brothers experienced all they way in the East. They would draw upon gruesome tales of terrible monsters and heroic tales of themselves defeating these monsters, as they surmised their own travels in the future to take shape like those their elders must be experiencing. The ideas often than not originated in the mind of the young Polo, spirited as he was, but it took someone like Giuliano to agree for the boys to enjoy their fantasies to the utmost.

As soon as Marco was old enough, the two would venture in their fantasies beyond the Polos’ property, and into the city of Venice, where no imaginary foe could be defeated. The two men, mostly through the quick tongue of Marco, came in contact with many merchants far and wide, some from the west, but also from the south and east, whose stories would entice them further and breathe new life into their own imaginations.

Like this, the two young men’s time passed, until 1269, when Maffeo and Niccolò’s ship could be spotted on the horizon once again.

The two had told fabulous stories of their years of travel, and now being twenty and fifteen years old respectively, Giuliano and Marco sought to join Marco’s father and uncle on their next adventure.

They did set off for their second journey only two years later, in 1271, and this time Marco and Giuliano joined them on their travels.

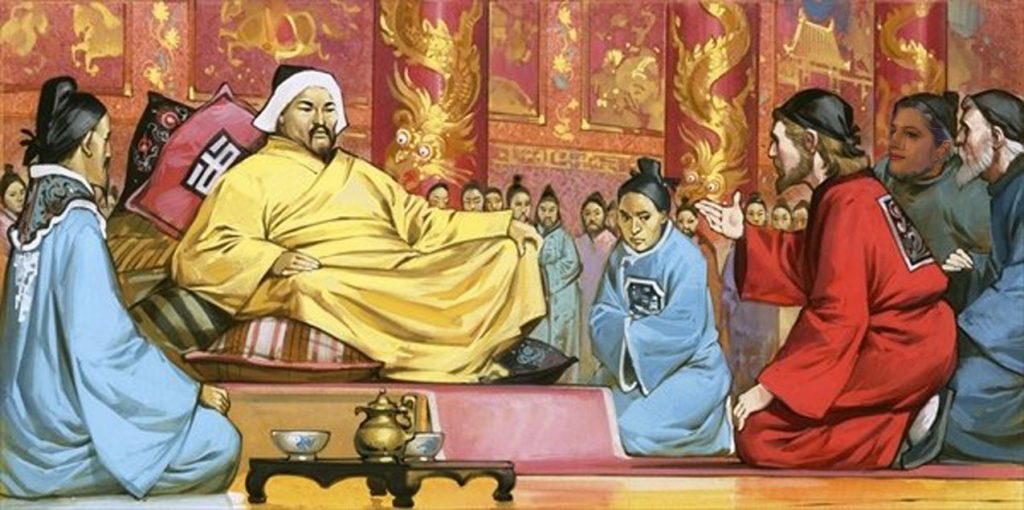

According to evidence found, the four merchants travelled all the way to Karakorum, which had until 1260 been the capital of the Mongol Empire. They continued on to Lanzhou, and from here to the khan himself, who now had found his residence in modern-day Beijing. Within China, they travelled to Chengdu, nowadays in the province of Sichuan, where Marco Polo wrote about the Anshun Bridge, amongst others, which crosses the Jin River in Chengdu. The bridge continues to stand until today. From there, Marco and Giuliano, as well as Marco’s father and uncle returned to Beijing, and continued to travel to Hangzhou, undoubtedly observing the aftermath of the taking of the capital city, which “the Mongols took … in 1276.”[1] Unquestionably, the travellers must have also been aware of the fact that “the last resistance fleet was defeated near modern Hong Kong in 1279.”[2]

By this point, the Yuan dynasty ruled all of China, and it would continue to do so until 1368. It is rumored that during his twenty years of travelling through China, Marco Polo at one point held the post of governor of Yangzhou, in which he surely would be able to confirm that, although foreign, the Mongol government “held examinations and made other gestures toward the Confucian tradition.”[3]

As a final mission, the Polos and Giuliano were tasked with escorting the Blue Princess, Koekecin, to her future husband, the Ilkhanate khan. This occurred in 1291, when Koekecin was only seventeen years old. The party of merchants left the port of Quanzhou early spring of that year, leaving for the direction of home. While at sea, Niccolò became ill of an unknown disease. Before they had reached the court of the Ilkhanate khan, Niccolò had passed away, and the now former party of four merchants had lost one of its members. Nevertheless, in 1293, they successfully carried out their mission given to them by Kublai Khan, and returned to Venice two years later, in 1295.

By this time, Venice found itself in war, and Marco, the never satiated youth that he was, decided to join the war. Giuliano, of much gentler nature, helped Maffeo, his former master, with the burial and the accompanying ceremony of his brother, Niccolò, who had died at sea. Once this had been completed, and Marco had engaged at war, Maffeo offered Giuliano to share his now full ownership of their merchandise store in Venice, which had solely passed to him after his brother’s death and Marco’s decline to engage in war instead. Giuliano, who had also lost his mother during the time he had travelled through Asia, had no other family left, and so accepted Maffeo’s offer. All this occurred in 1296.

Soon thereafter, Giuliano and Maffeo receive word that Marco has been captured and imprisoned in Genoa during his escapades at war. This causes both men a lot of grief, and Giuliano, so stricken by this news, decides to start noting down the two friends’ experiences in the Far East. Next to selling the wares the Venetians brought along from abroad, Giuliano now spends hours of his time recording and compiling memories and evidence of their time spent in the boundaries of Kublai khan’s reign.

Giuliano spends hours upon days quietly in his room, one moment lost in his memories, and the next making sure to note down every detail either he or his life-long friend would ever have remembered in all their time together. As time goes on, Giuliano spends more time in his room and only seldom leaves to visit the shop, he develops an illness with symptoms not unlike to those of which Niccolò had succumbed to while at sea returning to Venice only years earlier.

In 1299, Marco is released from incarceration, and returns to his uncle and his friend in Venice. Through the wares they had taken with them while travelling throughout the Asian continent, Maffeo had been able to amass a great volume of wealth, a portion of which he now used to finance his nephew Marco a house. This house would later go on to gain an incredible amount of fame by the name of Corte del Milion. Equally taken aback with the development of Giuliano’s serious illness as Giuliano had been when he had received the news that his friend had been incarcerated, Marco asked Giuliano to move into his new home with him, in hope of helping his friend with improving Giuliano’s condition and defeating the mysterious illness his father had previously contracted also, to which Giuliano agreed.

With his friend’s noble efforts, Giuliano indeed agreed to take residence in Marco’s new home, and with the continuous effort of the local doctors, his condition started to improve. He showed Marco what he had been working on during his years in prison, the compilation of their memories together during their travels to the continent to the East. Seeing the tremendous amount of work and exertion Giuliano had put himself through the get as far as this at compiling their travels, Marco resolved to help his friend with his endeavor, and sought out a famous novelist of their time, Rustichello da Pisa, to help the two of them with the completion of the compilation.

Having seen to his friend’s aid, as well as having engaged a novelist of the time to help with creating a legacy of the two, Marco now decided that marriage would make his life complete. Indeed Marco had already had someone in mind, and having heard this, Giuliano was so worried that his friend might leave him again, that the doctor’s work had been for naught, and his illness took again a turn for the worse. Having already set the date of his wedding in 1300, Marco was set out to see it through, assured that by marrying and proving that he would not leave his friend, Giuliano would get better. The night before Marco’s wedding, however, Giuliano had breathed his last, and Marco’s loyal friend had sailed off without him.

Giuliano’s compilation that Marco had had the romance novelist edit, however, came to claim great fame, and has become what we now know today as The Travels of Marco Polo: [it] “was one of the most widely read books in Europe, circulating first in manuscripts that were hand copied, and then, after Gutenberg’s discovery of movable type, as an early published book.”[4] The work’s lack of credibility, had no doubt originated under Rustichello’s hand, as “[Rustichello], like many modern ghostwriters, felt no compunction about embellishing the truth to enhance the readability of his account.”[5]

Despite this, Giuliano’s influence had not been completely lost, as “one scholar has recently shown that Polo’s description of Chinese paper money is the most detailed account in any language. It explains how the Chinese made, employed, and replaced the notes.”[6]

Notes

[1] Wills, John E. Mountain of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP, 1994. Print. Page 199.

[2] Wills, 199.

[3] Wills, 199.

[4] Hansen, Valerie. The Open Empire: A History of China to 1800. New York: Norton, 2000. Print. Page 318-9.

[5] Hansen, 319.

[6] Hansen, 321.

JACQUELINE HEINZELMANN is a student at the University of Rochester. Jacqueline, who goes by Jackie, studies International Relations and East Asian Studies. When she is not busy writing essays for her various classes, she is probably reading. More by Jackie

JACQUELINE HEINZELMANN is a student at the University of Rochester. Jacqueline, who goes by Jackie, studies International Relations and East Asian Studies. When she is not busy writing essays for her various classes, she is probably reading. More by Jackie