Born in 900 A.D., Li Ruolin was the younger sibling of Li Cunxu, also known as Emperor Zhuangzong of the Later Tang, who formerly ruled the Jin State that had formed directly following the fall of the Tang Dynasty. Li Ruolin and Li Cunxu shared the father Li Keyong, but Princess Li was born the daughter of one of his concubines. This concubine was well acquainted with Li Keyong’s wife, Consort Dowager Liu, who accompanied Li Cunxi during many of his military campaigns and taught women how to ride horseback. Princess Li’s birth in 900 A.D. came 15 years after the birth of Li Cunxu. By that time, Li Keyong was living around Taiyuan (modern Taiyuan, Shanxi) and Li Cunxu’s mother, concubine Lady Cao, and Lady Liu his wife, had taken on the responsibility of raising the children of Li Keyong’s concubines. As Lady Cao was the mother of the heir, Li Cunxu, she had duties as the rightful Dowager Empress. Thus, Lady Liu became Li Ruolin’s primary caregiver.

Born in 900 A.D., Li Ruolin was the younger sibling of Li Cunxu, also known as Emperor Zhuangzong of the Later Tang, who formerly ruled the Jin State that had formed directly following the fall of the Tang Dynasty. Li Ruolin and Li Cunxu shared the father Li Keyong, but Princess Li was born the daughter of one of his concubines. This concubine was well acquainted with Li Keyong’s wife, Consort Dowager Liu, who accompanied Li Cunxi during many of his military campaigns and taught women how to ride horseback. Princess Li’s birth in 900 A.D. came 15 years after the birth of Li Cunxu. By that time, Li Keyong was living around Taiyuan (modern Taiyuan, Shanxi) and Li Cunxu’s mother, concubine Lady Cao, and Lady Liu his wife, had taken on the responsibility of raising the children of Li Keyong’s concubines. As Lady Cao was the mother of the heir, Li Cunxu, she had duties as the rightful Dowager Empress. Thus, Lady Liu became Li Ruolin’s primary caregiver.

Being of Shatuo blood, Princess Li’s high status came not from being ethnically Chinese, but rather from a long legacy within her family line of military generals. In order to decrease the probability of internal rebellion against the Tang Empire, following the An Lushan rebellion, the Shatuo people were taken advantage of under the Emperor Xianzong to divide and protect the empire. This helped to keep pressure from the Uyghurs and Tibetans under control. During the suppression of the Pan Xun rebellion, Zhuye Chixin was rewarded by appointment as a military commissioner and was given the imperial surname Li (李). Following his example, his son Li Keyong had earned the name “Son of the Flying Tiger” during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong’s son Emperor Yizong, because of his military prowess.

-300x279.png)

Being of privileged relation to the imperial court, Princess Li enjoyed special care from a young age. She lived in Taiyuan, Shanxi, as a child, showing an early thirst for knowledge. It was said that even as a toddler, Princess Li was pointing to calligraphic scrolls on the wall, crying until her caretaker would carry her to the wall for her to touch. The Five Dynasties period saw a great many military campaigns in order to rectify the dissolution of the Tang Empire. Education, therefore, was holding on to the golden era of Tang poetry and scientific discovery. The invention of woodblock printing allowed resources to spread more widely during the Tang, and being of the Imperial Court, Princess Li had access to literature and educational materials that had been passed on from Tang archives. Often times her maids found her bedroom empty in the mornings, and had to go searching the many rooms of the inner court only to find Li Ruolin crouched in a corner reading the poetry of Li Bai. Lady Liu had a special fondness for the child, and could be found in her chamber late in the evening with the little girl reading in her bedroom, after laying her other children to sleep.

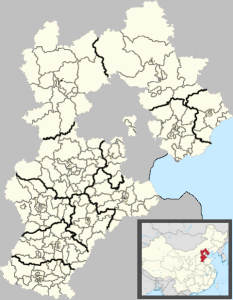

In the year 923, her brother became Emperor Zhuangzong of the Later Tang, whence relocating the capital from Chang’an back to Luoyang. Li Ruolin was relocated to Daming where Li Cunxu declared himself Emperor. By this time she was known within the imperial court as the principal teacher to her nephews and the heirs to the throne. As it is described regarding the Ban Family during the Eastern Han, there are instances in Chinese dynastic environments where it may have been possible for select women to gain an education close to that of their male equivalents:

“We will note many changing forms of this interweaving of ministerial idealism, family propriety, and careerism, right down to the end of the empire. In the particular mix of these values in these centuries, with its great emphasis on family propriety and discipline, it is not surprising to find that an unusual amount of attention was devoted to the importance of women as teachers and examples of virtue.” 1

The “ministerial idealism” Wills refers to is the expectation that sons that were well educated ought to rise up easily within the imperial line of rule, thus to insure the legacy of the family name. By this time, Li Ruolin had thoroughly taught herself to read and write, mostly due to pestering her brothers to see their academic materials. In particular, she had familiarized herself with the poetry of Li Bai, Du Fu, and Bai Juyi and read Zhang Yen Yuan’s catalog of Calligraphy Masterpieces. In the same way she had disappeared reading, Princess Li had an infatuation with calligraphy. She spent hours awake in the middle of the night practicing long, careful strokes; sometimes barely breathing for fear Lady Liu would wake up and reprimand her. Upon discovering her talent, Lady Liu had Princess Li appeal to her brother Emperor to educate the male heirs in calligraphy. Lady Liu made sure Princess Li emphasized attention on using calligraphy towards instilling sound Confucian ideals. It was said that “a classical education was supposed to be a preparation for a moral life, but especially for service as a minister of the emperor”2.

Emperor Zhuangzong was not a capable governor, often manipulated at the hands of his wife, Empress Liu. He accumulated wealth while running his armies via puppets. In this environment, Li Ruolin enjoyed the freedom to study, but became concerned with famine occurring in 926, just three years after Li Cunxu ascended to Emperor of the Late Tang. Cunxu’s successor, Li Siyuan, was an adoptive son of Li Keyong’s, and a more peaceful ruler than his predecessor. Li Ruolin appealed to his daughter, Princess Yongning, who agreed to help Ruolin establish an educational campaign in an effort to revitalize dynastic morale, but also to promote the education of women, drawing upon the influence of poets under the imperial reign of the only female ruler preceding her time, Empress Wu.

“The will to power was nowhere more directly seen than in the personality and career of the person who ruled the Chinese Empire in 700. Governing very effectively, strengthening the powers of the throne and of the central bureaucracy, this ruler was an astonishing anomaly, a living affront to some deeply rooted proprieties, for the simple reason that she was a woman, the only woman ever to occupy the position of emperor, huangdi, in her own name.”3

Ruolin was taught the Confucian ideals through her caretakers at Taiyuan, but she was indignant on having remained standing by as people starved under Cunxu’s reign. She turned to literature for consolation, and was inspired by stories like Yuan Zhen’s Ying Ying. Hansen describes Yuan Zhen as “a great prose stylist, succeeds in realizing one of the most sympathetic and strong women in Chinese literature. Writers in subsequent centuries often retold this intense story of thwarted love.”4 Despite her frustration, Ruolin understood the costs of acting too brashly, and instead read and practiced calligraphy while privately documenting the incompetence of what she saw as power hungry mongrels disrespecting the sovereignty of the scholarly dynastic model for ruling the imperial court.

In 936, her project was interrupted when she met the Later Jin Emperor, Shi Jingtang. Shi Jingtang was a green ruler having been handed the Tang army after a series of military mishaps in negotiations with the Khitan. He had married Princess Yongning, thereby learning of Li Ruolin’s calligraphic prowess, and decided to take her as his concubine during the Later Jin. Although Ruolin was unable to continue the research project, Shi needed her writing skills to dictate military correspondence. By this time she was 36, and was more of an asset than a prize concubine. Regardless, she became pregnant just two years later. Approaching her 40s, however, there were significant prenatal complications, which led to a miscarriage, and provincial magnates rumored that severe post-partum depression left her a nuisance to the emperor, as she could no longer draft military letters. As a result, Li Ruolin was dismissed from the inner court, whereupon Ruolin requested relocation to Duhuang, where her caretaker Lady Liu had once described her distant relative Zhang Yichao as having reclaimed land there. Hansen says “Zhang Yichao reclaimed the land from Tibetan rule called Dunhuang, some 700 miles due west of the Tang capital, populated by Chinese and non-Han peoples. He was succeeded by his son, and then in 923, by the Cao family, who continued to rule as military governors after the fall of the Tang dynasty”5. When she arrived there, Li Ruolin took up Buddhist practices and monastic life to come to terms with her depression. Her entire life up until this point, she had felt misrepresented for being a woman. She had educated herself in secret, found a way to combat the incompetent rule of her relative Cunxu, or Emperor Zhuangzong, and even became a scribe and concubine to Jin Emperor Shi Jingtang.

“The power of female sexuality was widely recognized, and in the Daoist tradition some of the most powerful metaphors of the unchanging Way were feminine metaphors of accepting passivity, taking the lower part, and the ‘gate of all mysteries.’ But even in this nearly balanced version the correspondences showed that the female should be passive, and that her role should be “inside” the household, while the male dealt with the outside world.”6

To this end, Li Ruolin felt that her position as a woman left her ultimately unfulfilled, but she looked back nostalgically and thought that she’d done the best she could with the role she was given.

At this time, Buddhist philosophy as the mainstream religious practice had become interwoven with Confucianism and Daoism. During the 8th century, Buddhism was repressed along the Silk Road itself. By the mid- 9th century, Buddhism itself was banned, as described below:

“Blaming Buddhist monasteries for hoarding wealth and seeking to enlarge the tax rolls, the emperor took his first measures against the Buddhist establishment in 842 by ordering monks and nuns to return to lay life or to begin paying taxes.”7

While Li Ruolin was not recruited as a member of a lay association, many of the associations “joined together to raise money for large-scale building projects … the charters of these groups were written in beautiful characters and discuss Buddhist doctrine at length”8. She found her calligraphy skills useful for helping to draft charters. As Dunhuang was an important landmark along the Silk Road, by 959 Li Ruolin had established herself as a merchant in calligraphy. Despite her unusual circumstances, Ruolin had been graciously awarded a certificate from Emperor Jingtang legitimating her family name. Although she had no male relative to support her, she was fortunate enough to have the skills to survive. She found refuge with Buddhist lay associations of all women, who at certain times treated her as an enlightened being, because of her high level of education. Furthermore, given her exile, Ruolin’s merchant status proved a bit of a mystery, and she never did find refuge with her Shatuo relatives. In the end, there was a Muslim invasion, which destroyed Buddhist monasteries and usurped regions in Northwest China. Suddenly, she was at the mercy of her captors, and would probably have been traded into prostitution or as a concubine hadn’t she killed herself with the sharp end of her calligraphy brush in 962, before reaching her 63rd birthday. Her legacy as an educator left record of the period of Five Dynasties, during which the glory of the Tang faded, and the commercialization to be discovered in the Song left China dismantled and disoriented amidst a series of power hungry military campaigns. Her calligraphy is archived under the a pen name “Zhong Shao-Jing” after a little known calligrapher that had scribed under Empress Wu Ze Tian. By her death, the pressure of living at the hands of patriarchal rule was simply too much for her to take.

Works Cited

1 Wills, John E.. Mountain of Fame : Portraits in Chinese History. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 1996. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 12 December 2015. Page 91.

2 Wills, 92.

3 Wills, 128.

4 Hansen, Valerie. The Open Empire: A History of China to 1800. Second Ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015. Web. Page 213.

5 Hansen, 249.

6 Wills, 132.

7 Hansen, 219.

8 Hansen, 254.

Further Resources

“Li Cunxu.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Web.

“Silk Road Transmission of Buddhism.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Web.

“Tang Dynasty.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Web.

“Later Tang.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Web.

“Daming County.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Web.

CAROLINE STERLING I’am an East Asian Studies major, focusing primarily on learning Mandarin. I participated in a language intensive program in Beijing during Spring 2015. I have been in After Hours co-ed a cappella for four years. Meliora! More by Caroline

CAROLINE STERLING I’am an East Asian Studies major, focusing primarily on learning Mandarin. I participated in a language intensive program in Beijing during Spring 2015. I have been in After Hours co-ed a cappella for four years. Meliora! More by Caroline