| Time Period | Qin Dynasty |

| Geographical Region | Northern China |

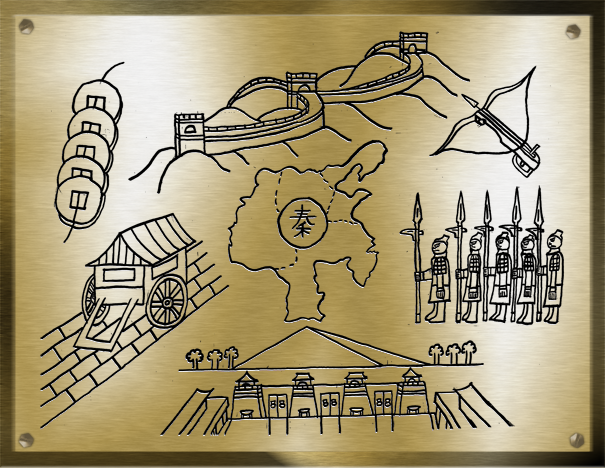

| List of Symbols |

|

The Qin Dynasty, although renowned for its brutality and paranoid emperor, should also receive a legacy of great achievements given its astonishing and monumental impressions embedded in Chinese history. Despite overshadowed by his less appealing side, one should not overlook the ambitions of China’s first emperor, Shi Huangdi, who integrated geographical and social aspects into one state, which would constitute the ideology of unification for future dynasties. The idea of “China” would not exist today without the successful consolidation of power by the Qin Dynasty.

The territorial map of the conquests under the Qin symbolizes probably its greatest accomplishment, the unification of the Seven Warring States in 221 BC. The dashed lines represent the former boundaries of the individual kingdoms prior to Ying Zheng’s (Shi Huangdi) conquests. The location of the Qin Dynasty’s landscape on the plaque conveys one specific message: without the central goal of establishing a single state, no other unified architectural, political, or social projects could exist.

The Great Wall, consistently seen as the quintessential symbol of Chinese culture, possessed origins during the Qin Dynasty. After securing control of the Qin Empire, Shi Huangdi sought to protect his territory from the northern barbarians. His solution was to construct a wall spanning the empire’s northern border, hence the image’s location on the top of the plaque. Although serving as a defensive fortification, the wall also represented a unity of a people. The Great Wall did not exist solely as a newly erected structure, rather a great part of its construction laid in the joining of previously built walls prior to Qin’s unification. In addition, the wall separated an agricultural Chinese culture from the nomadic tribes. What the Great Wall conveys in this plaque is the integration and isolation of a common lifestyle as well as a geographical boundary.

Prior to his death, Emperor Shi Huangdi ordered the design and construction of his final resting place. The underground tomb, possibly one of the greatest burial sites in history, emulates much of the divine aspects Shi Huangdi expressed in his imperial rule. Sources say a map of the Qin conquests comprised the floor of the complex, including natural features, such as rivers flowing with mercury, in addition to a palace and a ceiling filled with gems to symbolize the heavens. The presence of Shi Huangdi’s tomb in this plaque projects the idea that the Qin possessed great technological advancements and resources to be able to construct such an impressive feat of engineering.

In addition to the lavish tomb itself, Shi Huangdi also commanded builders to create clay soldiers to take to the afterlife, hence the origins of the terracotta army. Each soldier, with lifelike human qualities and armor, as well as genuine military equipment, served to protect the emperor even in death. The terracotta army holds a position in this plaque to signify the importance of the military during the Qin period. It was the army that accomplished unification and gave Shi Huangdi his power. The military proved an integral part in China’s foundation, thereby earning a position in the Qin’s greatest achievements.

The widespread use of the crossbow during the Qin period provided its army with a deadly weapon, given its easy use greater power than a traditional bow. But why should a common weapon used throughout Chinese history be given such prestige in the Qin Dynasty? Given the importance of the military, the crossbow proved an effective piece of equipment to assist Ying Zheng’s army in establishing his dream of a unified empire. The Qin’s ability to successfully mass-produce and equip its armies with this weapon, despite its complex design, demonstrates the advanced production capability of this early dynasty.

With the foundation of the Qin Dynasty completed, Ying Zheng then needed to build its economy. With seven different kingdoms under his control, the emperor work towards standardizing the currency. Known as the banliang, the circular coin boasted a square hole in its center and replaced earlier forms of financial methods of payment, thus the appearance of China’s first unified currency. The single form of payment therefore centralized trade and commerce within the new empire. The Qin Dynasty gave birth to numerous “firsts” in Chinese history, and the banliang proved no exception given its use under later dynasties.

As with the creation of a single currency, the Qin also desired to ease the accesses to trade and commerce across a vast territory. To accomplish this task, the dynasty took part in a road construction project that rivaled that of ancient Rome. In addition, the wheel also received a standardized measurement in relations to the width of the roads as means to make transportation more efficient. The system of roads and the establishment dimensions of the wheel projected the Qin’s desire to make the empire a smaller and accessible place.

The goal of this plaque serves to portray the positive, lasting effects of the Qin Dynasty. Aside from the chaos that took place under Emperor Shi Huangdi, one can learn of the great consolidation tactics within the military, economic, and social reforms. Whether the construction of a massive fortification or the production of a simple coin, the idea of unification prevailed throughout the Qin Dynasty, and eventually paved the way for the rise of future Chinese dynasties.

I am Garwin Leung, and I study history as my college major with a focus on East Asia. I was born in New York and in my free time, I enjoy spending time with friends. More by Garwin