| Time Period | High Tang Dynasty |

| Geographical Region | Chang’an, but also other regions within the vast geographical area under Tang control |

| List of Symbols |

|

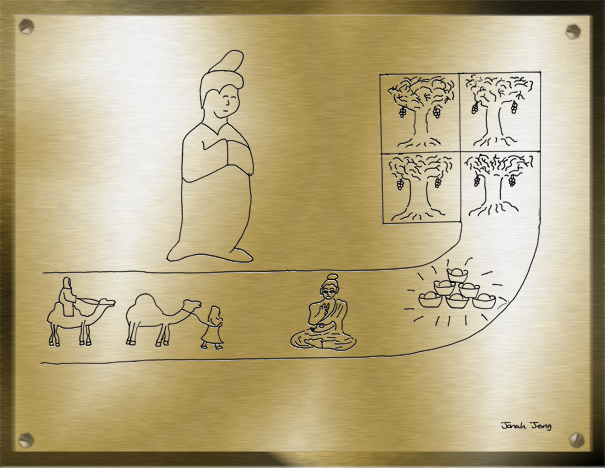

Seen together, the symbols on my plaque are meant to represent the period in the Tang Dynasty preceding the An Lushan Rebellion. Often called the Golden Age of China or the “High Tang,” this stretch of Chinese history was characterized by increased cultural and commercial contact between Chinese and non-Chinese, including but not limited to the exchange of precious metals and religions, as well as shifting standards of beauty and fashion for women. All these aspects are represented in my plaque, which I believe captures the essence of the High Tang, albeit imperfectly. If this plaque had been unearthed in an archaeological dig sometime after the Tang, I believe it would have been at least somewhat instructional to the archaeologists of what life was like during the Tang cultural renaissance.

The first symbol I included was the two-by-two grid of mulberry trees, which represents the equal field system. The presence of the trees is meant to cue viewers into realizing that the squares signify plots of land, whose uniform size would hopefully then bring to mind the equal field system. It is true that this agricultural model is traditionally associated with the Northern Wei Dynasty, established as it was by Dowager Empress Feng to incentivize the nomadic Tabgach to settle down and be subject to a land tax. Moreover, during the Tang, the equal field system was becoming increasingly ill fitted to the dynasty’s expanding economy. Nonetheless, I still included it as a symbol because, although the equal field system is indeed primarily credited to the Northern Wei, it was not until after the An Lushan Rebellion that this system of agriculture completely disappeared. As such, the High Tang, which occurred before the rebellion, could be thought of as containing the final traces of a soon-to-be-extinct agricultural mode, and thus I felt the equal field system was an important component of the dynasty’s legacy.

The second symbol overlaps with the first in the image of the mulberry tree, but whereas the tree’s function in the first symbol was simply to signify agriculture, its purpose here is to represent silk. The bottom right box of the symbol for the equal field system leads directly into a path that winds westward. This path, my second symbol, signifies the Silk Road, the primary means of trade between the Chinese and the non-Chinese during the High Tang. By having the Chinese end of the route begin at the mulberry tree, I am indicating that silk was China’s primary export during this time, and that it was transported via this highway of trade linking various peoples located thousands of miles apart. My third symbol, a caravan of camels and eastbound traders drawn directly on the image of the Silk Road, is meant to highlight the motif of travel, and additionally the cross-cultural contact that existed during this time.

The fourth and fifth symbols reveal two key goods that were exchanged on the Silk Road during the High Tang, hence their placement on the symbolic Silk Road itself alongside the aforementioned camels. The fourth symbol, a pile of golden nuggets whose material composition is made apparent by both the recognizable shape of the nuggets and the familiar shine radiating off of them, unsurprisingly represents gold. The fifth, on the other hand, signifies an immaterial object of trade: Buddhism, which gained entry into Chinese culture by way of Central Asian and Indian merchants traveling on the Silk Road. I chose to represent Buddhism through the instantly recognizable figure of the Buddha.

My final symbol takes the form of a typical Tang Dynasty woman and seeks to emphasize the way the standards of beauty for women underwent dramatic shifts in the years leading up to this period. By the time of the High Tang, these standards ran the gamut from a more robust body shape to looser clothing, all of which are represented in the figure of the woman. In contrast to the Song Dynasty some half a century later, when foot binding would become a cultural staple, the High Tang was a time of relative freedom for women.

Altogether, these symbols paint a picture of thriving culture both within China’s own borders and extending outward to the dynasty’s foreign neighbors/trade partners. The visual prominence of the Silk Road on my plaque is an indication of its importance during this period, as is the sheer number of symbols (5 out of 6) that pertain to it in some way. On the other hand, neither did I want to diminish the significance of domestic cultural changes, so I made the figure of the woman, though just one symbol, take up more space than any other symbol on its own. In the way my plaque unites the motif of cultural exchange across borders and shifting social mores domestically, I believe it is a legitimate representation of the High Tang Dynasty. A note: I would have added symbols indicating the civil service exams and Emperor Wu Zetian, except I did not know how to represent either in a way that was immediately recognizable.

JONAH JENG is in the process of completing a double degree in Film & Media Studies and Brain & Cognitive Sciences, as well as a Take-Five in Chinese Language & Culture. He loves writing and cinema, two passions that converge in his blog at jonahjeng.wordpress.com. More by Jonah

JONAH JENG is in the process of completing a double degree in Film & Media Studies and Brain & Cognitive Sciences, as well as a Take-Five in Chinese Language & Culture. He loves writing and cinema, two passions that converge in his blog at jonahjeng.wordpress.com. More by Jonah