| Time Period | The Jesuits in China: Late Ming Dynasty, Early Qing Dynasty |

| Geographical Region | Macau, Beijing |

| List of Symbols |

|

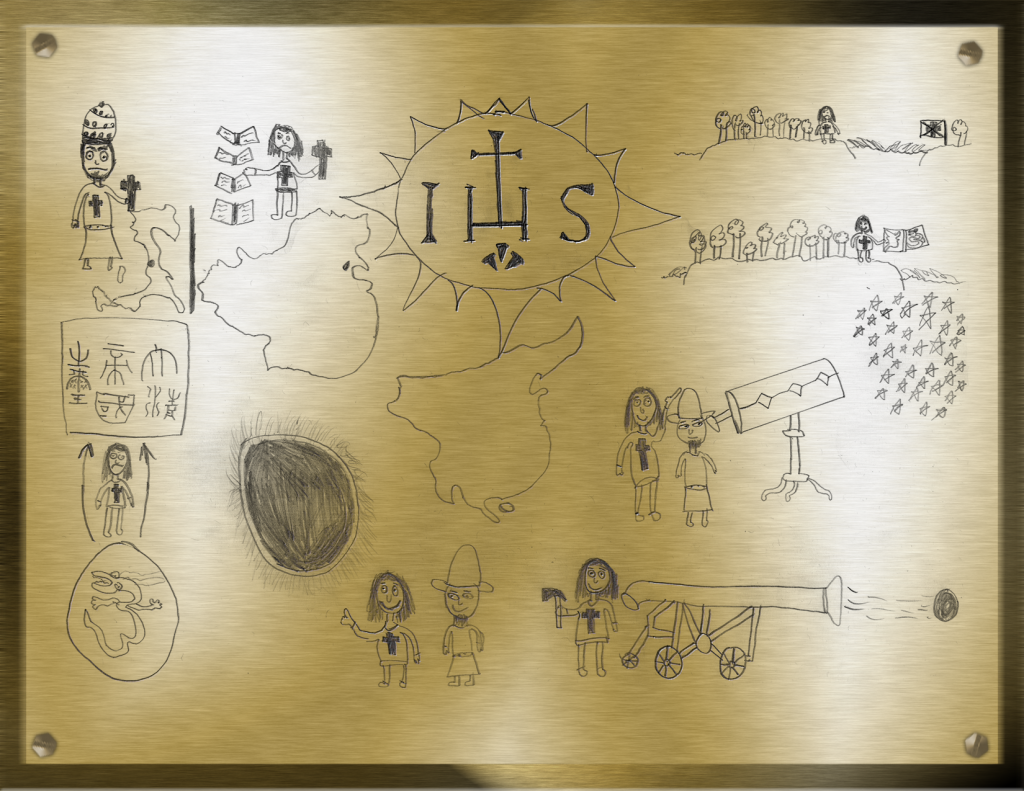

The Jesuits’ missions to China during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties formed a very interesting time in history for both Catholicism and China. The Jesuits gave the Chinese people of the time a glimpse into the European world, advancing some of their scientific and militaristic models in the process. The Golden Plaque that is being displayed here is filled with symbols and drawings of this fascinating time, starting with the Jesuits’ integration into Chinese society and ending with the Chinese Rites Controversy.

The most prominent symbol shown is that representing the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits. The three letters in this symbol, IHS, stand for Jesus and were adapted from the Greek “Ihsous”, which is what Jesus was referred to as in the Gospels. Above IHS is a cross, the symbol of Christianity, and below appears to be three nails, the three that were used to nail Jesus to the cross. Below the symbol of the Jesuits is the map of China during the Ming dynasty, the first time the Jesuits made contact with the Chinese. This combination of the Jesuit symbol and the Chinese map portrays the mission of the Jesuits’ quite clearly: to go to the foreign land of China and show them the glory of God.

Starting at the top right of the plaque, there is a drawing of a Jesuit, made distinct by his long hair, which was common for Catholic missionaries at the time. This Jesuit in particular represents the first Jesuit to enter China, Matteo Ricci. He has arrived at the island of Macau, which is just off the coast of China. However, he is being denied access into China as they do not allow foreigners, and in this case Catholics, onto their lands. This is represented in the plaque by the flag with a cross symbol on it that has been crossed out on the mainland of China. Continuing down clockwise, Ricci is shown to dedicate all of his time and energy on Macau into studying the language of Chinese and learning everything he can about it. After years of waiting and studying, Ricci and his fellow Jesuits were finally allowed into the Chinese empire. Ricci became the first Westerner allowed inside the walls of the forbidden city, where he impressed the Wanli Emperor using his scientific knowledge, especially that of astronomy.

Continuing down the plaque are the many scientific advancements that the Jesuits introduced to the Chinese. First, the Jesuits were very good astronomers, and were able to start a scientific branch of astronomy in the Ming court. The plaque details this with the Jesuit figure showing a Chinese scholar the stars through a telescope. Additionally, the Jesuits showed the Chinese empire how to build western style cannons, which were used for devastating effects in warfare. The most impressive of the scientific prowess shown by the Jesuits in China, however, was their ability to predict solar eclipses—an ability that was demonstrated in winning competitions with local scholars. In the symbol at the bottom of the plaque, this Jesuit could either be Matteo Ricci or Johann Adam Schall von Bell, who impressed the Qing Dynasty after they overtook the Ming Dynasty by accurately predicting a solar eclipse.

The bottom left hand corner of the plaque represents the struggle the Jesuits in China underwent during the bloody transition from Ming Dynasty to Qing Dynasty. The bottom symbol is the imperial seal of the Ming Dynasty, while the top symbol is the imperial seal of the Qing Dynasty. In between the two is a Jesuit representing how many were caught in between the two dynasties. Some welcomed the transition, such as Schall, and were quick to impress the Qing, while others sided with the Ming Dynasty. Many Jesuits were jailed during this time or even had to fight on the battlefield.

The final symbol on this plaque is in the top left. It shows the Pope, the leader of the Catholic Church, on top of a map of Italy, the hub of Catholicism. Here he is holding a cross. Opposite him is a Jesuit on top of China, holding a cross and the four essential books of Confucianism. This symbol represents the Chinese Rites Controversy, in which the Vatican did not believe it was right for the Chinese to continue their ancestral rites and traditional Confucian practices, while the Jesuits believed that the practices were acceptable to a certain extent and that the rights and practices of Confucianism could be linked back to Catholicism. Other orders in the Catholic Church, such as the Franciscans and Dominicans, sided with the Vatican and reported the behavior back to Rome. This caused a divide between China and the Vatican, leaving the Jesuits somewhere in the middle, many to die unceremoniously without ever being able to get back to Rome. The cross that the Jesuit is holding in this symbol represents their devotion to the Catholic Church, while the four books represent their respect to the ancient Chinese ancestral and Confucian rites.

Taken together, this plaque, depicting the Jesuits’ missions in China, gives a fascinating glimpse into the journey and influence that the Jesuits had on the Ming and Qing dynasties. Furthermore, it shows the obstacles that the Jesuits faced in China, whether it be staying in Macau to learn the Chinese language and culture or the bloody dynastic change between the Ming and the Qing. Without words, this plaque offers a timeless view into the enthralling Jesuit mission in China.

PAUL EDWARD JOSEPH-BERNARD DUNHAM is a student at the University of Rochester with an expected graduation date of 2020. He is currently focusing on studying both Mathematics and Chinese. He is also a passionate rock climber and nature enthusiast, as well as an avid guitarist and overall musician.