| Time Period | Late Sui Dynasty (604-617; Reign of Yang Guang) |

| Geographical Region | Eastern China (modern day, from Beijing all the way to modern day Hangzhou, some maps even indicate territory as far south as modern Guangdong) |

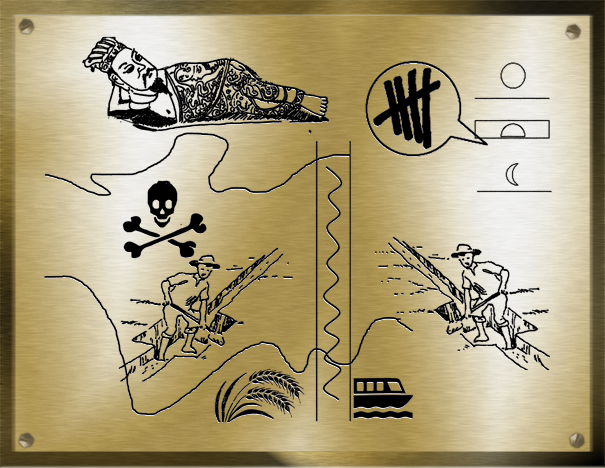

| List of Symbols |

|

Carl Sagan attempted to depict through symbols a message about human life to aliens. The images he chose were not just to point to specific objects which exist on Earth, but to tell a story by putting the objects together in context. My plaque attempts to not simply depict some waterways, transportation, crops, death, and the passing of time, but to create a story by the fact that they only convey significant meaning when juxtaposed together.

The Sui Dynasty only lasted three short decades, the last thirteen years of which marked the reign of one of China’s most exorbitant emperor’s, Yang Guang. The plaque is meant to focus specifically on the achievements and consequences of Emperor Yang Guang’s reign. After going through each symbol, it should become apparent that each symbol only makes sense in relation to the rest.

Following the end of the Han dynasty, China was in disunity for roughly three and a half centuries before being reunified under the Sui. Thus, one of the great legacies under Yang Guang, who will hereon be referred to as Emperor Yang, was the commission to build the Grand Canal. In the plaque, the Yellow River and Yangtze River are depicted, at the top and bottom to show their relative location. Connecting the two together, which is significant for trade routes, is the Grand Canal. The canal is depicted by two straight lines indicating its banks, and that it is man-made. So that we know it is a canal, and not a railway, there is a wavy line in the center depicting water. The Grand Canal was crucial for expediting the transportation of resources from the south to the north, because China’s largest natural rivers run only run from East to West. One of these resources was rice, which is symbolized by its plant at the bottom (or in the south) of the canal. Next to the rice symbol is a boat, which I put at the near the rice to indicate that the canal is often used for transportation of resources.

Emperor Yang took many trips along the canal on his own boats, which were typically several stories high, and enslaved thousands of people to tow it for him. To depict the hard labor of conscripted servants, there are two laborers digging on either side of the canal. Above the laborer on the right is the symbol for death, symbolizing that the laborer’s work was hard and resulted in the deaths of thousands. Despite its contribution to the economy, the Grand Canal itself is symbolic of what has been called genocide by Emperor Yang.

An important symbol at the top left is of Emperor Yang juxtaposed on top as a reclining Buddha. The emperor is relaxing while the peasant works painstakingly, and the emperor’s body is like a reclining Buddha. The first part is simply meant to signify Yang’s extravagance, because while he was consumed by hedonism, his regime extorted debilitating taxes from peasants to fund the Grand Canal project, as well as drafted thousands to perform the hard labor to make the canal possible. The reclining Buddha is a subliminal symbol, meant to give more context to the audience that Buddhism was prevalent during the Sui. Both Yang Jian, the first emperor of the Sui and Yang Guang’s brother, reinstated Buddhism as a state ideology, which is significant because Emperor Wu of Zhou had attempted to renew ancient Zhou ideals by banning Buddhism and Daoism (and refocusing on Confucianism). By putting the emperor’s head on the reclining Buddha, one should find their own interpretation, perhaps irony or a political message denouncing Yang. My attempt is to show that the emperor clearly supported and embodied the Buddhist teachings. Prominent Buddhist philosophers of the Sui, Jizang and Zhiyi, spearheaded the “Buddhism-renewal” during the Sui dynasty.

The final symbol, and perhaps most abstract, is meant to tie together the overall message of the plaque, which is ultimately a warning to future generations that selfish rulers’ time will be cut short. In order to symbolize time passing, there is the image of a sun on the horizon, followed by a setting sun, followed by a moon on the horizon. This shows the passing of time from day to evening. In order to show the quantifying of time, tally marks are used. Tally marks do not depict any one language’s numeric system, and are generally a universal sign of counting. This is meant to show that the days were being counted until Emperor Yang could be overthrown. Considered to be one of the most hedonistic, ludicrous, and lunatic Emperor’s in Chinese history, by the time Emperor Yang had enough time to stop enjoying himself, peasant rebellion was ubiquitous. In a meager attempt to expand Sui territory into modern Korea and Vietnam, as well as against Turks in the north, peasants were through with his cruel, irresponsible reign and Li Yuan was prepared to take office, becoming the first Emperor of the Tang.

Works Cited

Cotterell, Arthur. The Imperial Capitals of China: A Dynastic History of the Celestial Empire. Woodstock: Overlook, 2008. Print.

Cua, Antonio S. Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy. New York [u.a.]: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Hansen, Valerie. The Open Empire: A History of China to 1800. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015. Print.

Lee, Lily Xiao Hong, and A. D. Stefanowska. “Xiao, Empress of Emperor Yang of Sui.” Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2007. 356-59. Print.

Owen, Stephen. An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996. Print.

CAROLINE STERLING I’am an East Asian Studies major, focusing primarily on learning Mandarin. I participated in a language intensive program in Beijing during Spring 2015. I have been in After Hours co-ed a cappella for four years. Meliora! More by Caroline

CAROLINE STERLING I’am an East Asian Studies major, focusing primarily on learning Mandarin. I participated in a language intensive program in Beijing during Spring 2015. I have been in After Hours co-ed a cappella for four years. Meliora! More by Caroline